Preface to Lyrical Ballads. William Wordsworth 1. Famous Prefaces. The Harvard Classics Famous Prefaces. The Harvard Classics. 1. Preface to Lyrical Ballads William Wordsworth 1. THE FIRST volume of these Poems has already been submitted to general perusal. It was published, as an experiment, which, I hoped, might be of some use to ascertain, how far, by fitting to metrical arrangement a selection of the real language of men in a state of vivid sensation, that sort of pleasure and that quantity of pleasure may be imparted, which a Poet may rationally endeavour to impart. I had formed no very inaccurate estimate of the probable effect of those Poems I flattered myself that they who should be pleased with them would read them with more than common pleasure and, on the other hand, I was well aware, that by those who should dislike them, they would be read with more than common dislike. The result has differed from my expectation in this only, that a greater number have been pleased than I ventured to hope I should please. Several of my Friends are anxious for the success of these Poems, from a belief, that, if the views with which they were composed were indeed realized, a class of Poetry would be produced, well adapted to interest mankind permanently, and not unimportant in the quality, and in the multiplicity of its moral relations and on this account they have advised me to prefix a systematic defence of the theory upon which the Poems were written. But I was unwilling to undertake the task, knowing that on this occasion the Reader would look coldly upon my arguments, since I might be suspected of having been principally influenced by the selfish and foolish hope of reasoning him into an approbation of these particular Poems and I was still more unwilling to undertake the task, because, adequately to display the opinions, and fully to enforce the arguments, would require a space wholly disproportionate to a preface. For, to treat the subject with the clearness and coherence of which it is susceptible, it would be necessary to give a full account of the present state of the public taste in this country, and to determine how far this taste is healthy or depraved which, again, could not be determined, without pointing out in what manner language and the human mind act and re act on each other, and without retracing the revolutions, not of literature alone, but likewise of society itself. I have therefore altogether declined to enter regularly upon this defence yet I am sensible, that there would be something like impropriety in abruptly obtruding upon the Public, without a few words of introduction, Poems so materially different from those upon which general approbation is at present bestowed. It is supposed, that by the act of writing in verse an Author makes a formal engagement that he will gratify certain known habits of association that he not only thus apprises the Reader that certain classes of ideas and expressions will be found in his book, but that others will be carefully excluded. This exponent or symbol held forth by metrical language must in different eras of literature have excited very different expectations for example, in the age of Catullus, Terence, and Lucretius, and that of Statius or Claudian and in our own country, in the age of Shakespeare and Beaumont and Fletcher, and that of Donne and Cowley, or Dryden, or Pope. I will not take upon me to determine the exact import of the promise which, by the act of writing in verse, an Author in the present day makes to his reader but it will undoubtedly appear to many persons that I have not fulfilled the terms of an engagement thus voluntarily contracted. They who have been accustomed to the gaudiness and inane phraseology of many modern writers, if they persist in reading this book to its conclusion, will, no doubt, frequently have to struggle with feelings of strangeness and awkwardness they will look round for poetry, and will be induced to inquire by what species of courtesy these attempts can be permitted to assume that title. I hope therefore the reader will not censure me for attempting to state what I have proposed to myself to perform and also as far as the limits of a preface will permit to explain some of the chief reasons which have determined me in the choice of my purpose that at least he may be spared any unpleasant feeling of disappointment, and that I myself may be protected from one of the most dishonourable accusations which can be brought against an Author, namely, that of an indolence which prevents him from endeavouring to ascertain what is his duty, or, when his duty is ascertained, prevents him from performing it. The principal object, then, proposed in these Poems was to choose incidents and situations from common life, and to relate or describe them, throughout, as far as was possible in a selection of language really used by men, and, at the same time, to throw over them a certain colouring of imagination, whereby ordinary things should be presented to the mind in an unusual aspect and, further, and above all, to make these incidents and situations interesting by tracing in them, truly though not ostentatiously, the primary laws of our nature chiefly, as far as regards the manner in which we associate ideas in a state of excitement. Humble and rustic life was generally chosen, because, in that condition, the essential passions of the heart find a better soil in which they can attain their maturity, are less under restraint, and speak a plainer and more emphatic language because in that condition of life our elementary feelings coexist in a state of greater simplicity, and, consequently, may be more accurately contemplated, and more forcibly communicated because the manners of rural life germinate from those elementary feelings, and, from the necessary character of rural occupations, are more easily comprehended, and are more durable and, lastly, because in that condition the passions of men are incorporated with the beautiful and permanent forms of nature. The language, too, of these men has been adopted purified indeed from what appear to be its real defects, from all lasting and rational causes of dislike or disgust because such men hourly communicate with the best objects from which the best part of language is originally derived and because, from their rank in society and the sameness and narrow circle of their intercourse, being less under the influence of social vanity, they convey their feelings and notions in simple and unelaborated expressions. Accordingly, such a language, arising out of repeated experience and regular feelings, is a more permanent, and a far more philosophical language, than that which is frequently substituted for it by Poets, who think that they are conferring honour upon themselves and their art, in proportion as they separate themselves from the sympathies of men, and indulge in arbitrary and capricious habits of expression, in order to furnish food for fickle tastes, and fickle appetites, of their own creation. Peter 2 9 But you are a chosen people, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, Gods special possession, that you may declare the praises of him who called you out of darkness into his wonderful light. 9 But ye. Like St. Paul in 2. Thessalonians 2 1. St. Peter turns with an outburst of triumph to the happier and more practical and attractive theme. All the most splendid titles of the old Israel belong in a fuller sense to these Hebrews who have joined the new Israel. With Peter Davison, Graham Crowden, Barbara Flynn, David Troughton. A surreal comedy series tracking the career of Stephen Daker, a young doctor who works for the. NEWS. news by mark mcginlay and kate white. DEAR READER, WELCOME TO ISSUE TWO OF THE PECKHAM PECULIAR, A FREE LOCAL NEWSPAPER FOR PECKHAM AND NUNHEAD. But you are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, an holy nation, a peculiar people that you should show forth the praises of him who has called you out of. Preface to Lyrical Ballads. William Wordsworth 1800. 190914. Famous Prefaces. The Harvard Classics.  In 1. Peter 2 5 they are bidden to aim at being what here they are said to be. Comp. Colossians 3 3 Colossians 3 5. A chosen generation. Better, a chosen, or elect race. As originally the clan of Abraham was selected from among all the families of the earth Amos 3 2, so out of the clan of Abraham after the flesh were these men selected to be a new clan, or race. They are not merely individuals selected one by one and left in isolation, but a tribe consolidated, only the bond henceforth is not merely one of common physical descent. A royal priesthood, an holy nation. These words are a direct quotation from Exodus 1. LXX. version. The Hebrew has a kingdom of priests, as in Revelation 1 6 according to the best reading which would mean, Gods organised empire, every member of which is a priest. Nor is the thought far different here.

In 1. Peter 2 5 they are bidden to aim at being what here they are said to be. Comp. Colossians 3 3 Colossians 3 5. A chosen generation. Better, a chosen, or elect race. As originally the clan of Abraham was selected from among all the families of the earth Amos 3 2, so out of the clan of Abraham after the flesh were these men selected to be a new clan, or race. They are not merely individuals selected one by one and left in isolation, but a tribe consolidated, only the bond henceforth is not merely one of common physical descent. A royal priesthood, an holy nation. These words are a direct quotation from Exodus 1. LXX. version. The Hebrew has a kingdom of priests, as in Revelation 1 6 according to the best reading which would mean, Gods organised empire, every member of which is a priest. Nor is the thought far different here.

The word royal does not seem intended to imply that every Christian is a king, or of royal birth though that, of course, may be shown from elsewhere, but describes his belonging to the King as we might speak of the royal apartments, the royal borough, the royal establishment, or even of the royal servants. The substitution, therefore, of royal priesthood for kingdom of priests brings out more clearly the personal relation to the Personal King. But if the writer had said royal priests, the notion of organisation would have slipped out of sight altogether. By way of compensation, therefore, it is restored in the substitution of priesthood see Note on 1. Peter 2 5 instead of priests. This, and the next phrase, an holy i. Israelite nation as they stood beneath Mount Sinai. This must be taken into consideration in dealing with the doctrine of the Christian ministry. The sacerdotal office was as common to all Israelites under the Law as it is to all the new Israel under the Gospel. A peculiar people. This curious phrase is literally, a people for a special reservation. It is, no doubt, intended to represent Exodus 1. Greek and the Hebrew, the variation being due to a recollection of the Greek of two other passages of the Old Testament Isaiah 4. Malachi 3 1. 7. The word rendered peculiar means properly making over and above, and would be represented in Latin by the word peculium, which means a mans private pocket money, as, for instance, the money a slave could make by working over hours, or such as a wife might have apart from her husband. When children speak of a thing being their very own it exactly expresses what we have here. From this sense of making over and above, by working out of hours, the word comes in other places to mean earning by hard work, in such a way as to establish peculiar rights of property over the thing earned. So in Acts 2. 0 2. St. Paul is probably thinking of the passage of Isaiah above referred to, both the hard earning and the special possession are intended the Church of God, which He won so hard for His very own, by His own blood. Here, perhaps, the thought of earning is less obvious, and it means a people to be His very own. Comp. Thessalonians 5 9, and Ephesians 1 7, where according to Dr. Lightfoot it means for a redemption which consists of taking possession of us for His own. That ye should shew forth the praises. This is an adaptation, though not exactly according to the LXX., of Isaiah 4. St. Peters mind by the word rendered peculiar. The word praises is put here in accordance with the English version there. The Greek means virtues, or powers, or excellencies, a rare word in the New Testament see 2. Peter 1 3. And the word for shew forth, which is nowhere else found in the New Testament, means by rights to proclaim to those without what has taken place within. This strict signification is very suitable here. St. Peter says that God has taken us for a people peculiarly near to Him, and the purpose is, not that we may stand within His courts and praise Him, but that we may carry to others the tidings of what we have been admitted to see. This was the true function of the old Israel, Do My prophets no harm Psalm 1. They were not elect for their own sake, but to act as Gods exponents to the world. This function they abdicated by their selfish exclusiveness, and it has descended to the new Israel. St. Peter and St. Paul are at one. Of him who hath called you out of darkness. This is to be understood of the Father, not of Christ. For one thing, the act of calling is almost always ascribed in the New Testament to God Himself and for another thing, it is probable that St. Peter regards our Lord as Head of this people of God, just as He is corner stone of the Temple, and High Priest of the hierarchy. The act of calling literally it is, who called, not who hath called was that of sending the preachers of the gospel to them, i. St. Paul and his followers comp. Peter 1 1. 2 1. Peter 1 2. 5. Here again, then, we have St. Peter speaking in praise of St. Pauls mission, and, indeed, speaking in the same tones of unbounded admiration His marvellous light. But could Hebrew Christians be said to have gone through so great a change in becoming believers Had they been in darkness We may answer that St. Peters use of the word marvellous is no affectation of sympathy. He himself found the change to be what he here describes, therefore there is no difficulty in supposing that other Hebrews should have found it so too. Besides which, the state of the Jews immediately before Christ and without Him is often described as darkness. See Matthew 4 1. Luke 1 7. 9. This very passage is quoted a few years later by St. Clement of Rome chap. Dr. Lightfoot has clearly established that St. Clement was a Jew. Verse 9. But ye are a chosen generation. The pronoun ye is emphatic. St. Peter is drawing a contrast between the disobedient and unbelieving Jews and Christian people whether Jews or Gentiles he ascribes to Christians, in a series of phrases quoted from the Old Testament, the various privileges which had belonged to the children of Israel. The words, a chosen generation, are from Isaiah 4. The Cornerstone is elect, precious the living stones built thereupon are elect likewise. The whole Christian Church is addressed as an elect race, one race, because all its members are begotten again of the one Father. A royal priesthood. Instead of holy, as in ver. St. Peter has here the epithet royal. He follows the Septuagint Version of Exodus 1. Hebrew has a kingdom of priests. The word royal may mean that Gods elect shall sit with Christ in his throne, and reign with him Revelation 3 2. Revelation 5 1. 0, and that in some sense they reign with him now over their lower nature, their desires and appetites or, more probably, the priesthood of Christians is called royal because it belongs to the King a priesthood serving Jehovah the King, just as we speak of the royal household Weiss, quoted by Huther. An holy nation. Also from Exodus 1.

The word royal does not seem intended to imply that every Christian is a king, or of royal birth though that, of course, may be shown from elsewhere, but describes his belonging to the King as we might speak of the royal apartments, the royal borough, the royal establishment, or even of the royal servants. The substitution, therefore, of royal priesthood for kingdom of priests brings out more clearly the personal relation to the Personal King. But if the writer had said royal priests, the notion of organisation would have slipped out of sight altogether. By way of compensation, therefore, it is restored in the substitution of priesthood see Note on 1. Peter 2 5 instead of priests. This, and the next phrase, an holy i. Israelite nation as they stood beneath Mount Sinai. This must be taken into consideration in dealing with the doctrine of the Christian ministry. The sacerdotal office was as common to all Israelites under the Law as it is to all the new Israel under the Gospel. A peculiar people. This curious phrase is literally, a people for a special reservation. It is, no doubt, intended to represent Exodus 1. Greek and the Hebrew, the variation being due to a recollection of the Greek of two other passages of the Old Testament Isaiah 4. Malachi 3 1. 7. The word rendered peculiar means properly making over and above, and would be represented in Latin by the word peculium, which means a mans private pocket money, as, for instance, the money a slave could make by working over hours, or such as a wife might have apart from her husband. When children speak of a thing being their very own it exactly expresses what we have here. From this sense of making over and above, by working out of hours, the word comes in other places to mean earning by hard work, in such a way as to establish peculiar rights of property over the thing earned. So in Acts 2. 0 2. St. Paul is probably thinking of the passage of Isaiah above referred to, both the hard earning and the special possession are intended the Church of God, which He won so hard for His very own, by His own blood. Here, perhaps, the thought of earning is less obvious, and it means a people to be His very own. Comp. Thessalonians 5 9, and Ephesians 1 7, where according to Dr. Lightfoot it means for a redemption which consists of taking possession of us for His own. That ye should shew forth the praises. This is an adaptation, though not exactly according to the LXX., of Isaiah 4. St. Peters mind by the word rendered peculiar. The word praises is put here in accordance with the English version there. The Greek means virtues, or powers, or excellencies, a rare word in the New Testament see 2. Peter 1 3. And the word for shew forth, which is nowhere else found in the New Testament, means by rights to proclaim to those without what has taken place within. This strict signification is very suitable here. St. Peter says that God has taken us for a people peculiarly near to Him, and the purpose is, not that we may stand within His courts and praise Him, but that we may carry to others the tidings of what we have been admitted to see. This was the true function of the old Israel, Do My prophets no harm Psalm 1. They were not elect for their own sake, but to act as Gods exponents to the world. This function they abdicated by their selfish exclusiveness, and it has descended to the new Israel. St. Peter and St. Paul are at one. Of him who hath called you out of darkness. This is to be understood of the Father, not of Christ. For one thing, the act of calling is almost always ascribed in the New Testament to God Himself and for another thing, it is probable that St. Peter regards our Lord as Head of this people of God, just as He is corner stone of the Temple, and High Priest of the hierarchy. The act of calling literally it is, who called, not who hath called was that of sending the preachers of the gospel to them, i. St. Paul and his followers comp. Peter 1 1. 2 1. Peter 1 2. 5. Here again, then, we have St. Peter speaking in praise of St. Pauls mission, and, indeed, speaking in the same tones of unbounded admiration His marvellous light. But could Hebrew Christians be said to have gone through so great a change in becoming believers Had they been in darkness We may answer that St. Peters use of the word marvellous is no affectation of sympathy. He himself found the change to be what he here describes, therefore there is no difficulty in supposing that other Hebrews should have found it so too. Besides which, the state of the Jews immediately before Christ and without Him is often described as darkness. See Matthew 4 1. Luke 1 7. 9. This very passage is quoted a few years later by St. Clement of Rome chap. Dr. Lightfoot has clearly established that St. Clement was a Jew. Verse 9. But ye are a chosen generation. The pronoun ye is emphatic. St. Peter is drawing a contrast between the disobedient and unbelieving Jews and Christian people whether Jews or Gentiles he ascribes to Christians, in a series of phrases quoted from the Old Testament, the various privileges which had belonged to the children of Israel. The words, a chosen generation, are from Isaiah 4. The Cornerstone is elect, precious the living stones built thereupon are elect likewise. The whole Christian Church is addressed as an elect race, one race, because all its members are begotten again of the one Father. A royal priesthood. Instead of holy, as in ver. St. Peter has here the epithet royal. He follows the Septuagint Version of Exodus 1. Hebrew has a kingdom of priests. The word royal may mean that Gods elect shall sit with Christ in his throne, and reign with him Revelation 3 2. Revelation 5 1. 0, and that in some sense they reign with him now over their lower nature, their desires and appetites or, more probably, the priesthood of Christians is called royal because it belongs to the King a priesthood serving Jehovah the King, just as we speak of the royal household Weiss, quoted by Huther. An holy nation. Also from Exodus 1.

Shirtless Mario is a skin mod that lets the Italian fighter trade his iconic overalls for swim trunks. If you want to run old games and programs on Windows 7 you better download this patch. Works 100. Get everything you need for Video Games at the best price possible. Find the latest promo codes, coupons, sales and shipping offers. Thank us later

Shirtless Mario is a skin mod that lets the Italian fighter trade his iconic overalls for swim trunks. If you want to run old games and programs on Windows 7 you better download this patch. Works 100. Get everything you need for Video Games at the best price possible. Find the latest promo codes, coupons, sales and shipping offers. Thank us later-11.jpg) Renders and provides the skin in both the games UI and in matches, with a metal version as well. Some players have already started uploading video of shirtless Smash Mario in action and the results look pretty seamless. By the end of the year month I fully expect the bathing suit version to have made it into every previous Mario game. You can check out the mod for yourself here.

Renders and provides the skin in both the games UI and in matches, with a metal version as well. Some players have already started uploading video of shirtless Smash Mario in action and the results look pretty seamless. By the end of the year month I fully expect the bathing suit version to have made it into every previous Mario game. You can check out the mod for yourself here.

Library and playlist media management. Burning DVDs Note If you already have DVD burning software this is not an important requirementLightweight putting less stress put on your CPU and RAMGraphics processor acceleration. Convert other video files to MP4H. Plug ins for expandability.

Library and playlist media management. Burning DVDs Note If you already have DVD burning software this is not an important requirementLightweight putting less stress put on your CPU and RAMGraphics processor acceleration. Convert other video files to MP4H. Plug ins for expandability.  Video and audio enhancements through preferences. Lack of conflicts or playback problems with your system. MP4 PLAYERS WITH ENCODERS AND CONVERTERSPerhaps more than MP4 players, encoders encompass more of a black art in order to create high quality images and sound. There are numerous parameters that must be taken into account, such as the aspect ratio, key frame distance, resolution, frame rate and the bit rate variable or fixed at which the original material will be encoded are some of the primary settings to look for. What determines the need for which settings is the type of end delivery system the video will be played back and displayed on. The better MP4 players will also have a converter feature, allowing you to change from one file format to. Keep in mind that even though the H. CPU intensive process so youll want to make sure the computer you use can support the MP4 player you select. The Witcher series is 10 years old this month, and to mark the occasion CD Projekt Red released this teary lil clip. High end, professional encoders costing thousands of dollars not only use the best software, they throw in significant dedicated hardware at the problem. That said, there are some quality software solutions for well under 1,0. There are also free MP4 players, such as Real. Player that can be used to convert video in one file format to. MP4 FREE MP4 PLAYERS PART OF A NEW ERAAs we move into MPEG based player formats, its worth a brief review of the Moving Picture Experts Group MPEG standards designated for a variety of digital video formats, which have progressed in complexity and quality over the years. Each MPEG standard encompasses several parts. These represent evolutionary changes and improvements designed for particular applications. Older MPEG standards, such as MPEG 1, a very low bit rate format, were designed for content distribution on CDs. ComfortTuck IWB Holster is the most comfortable holster series on the market. Sage receptionists and breakroom philosophers have long taught that every day has its own emotion. Your week progresses from a case of the Mondays through Wednesday. Automatically formats, alphabetize, and prints bibliographies for free. It can also be encoded onto DVDs for low quality or high capacity playback. MPEG 2 was the next step and is the standard for DVD Video. It was also originally used for some over the air and satellite services. It can also be used for high definition HD, but lacks the efficiency and higher bit rates that MPEG 4 encoding handles. These parts within the respective MPEG specifications are important since different parts translate to different capabilities. For example, MPEG 4 AVCH. Advanced Video Coding is known as part 1. AVCH. 2. 64 is designed for high bit rate Blu ray content, but because of its range of bit rates and efficient encoding, it can also be essentially downsized and incorporated into Internet video distribution services. MP4 is in part 1. MPEG 4. To be clear MP4, with its file extension of. Search the worlds information, including webpages, images, videos and more. Google has many special features to help you find exactly what youre looking for. BibMe Free Bibliography Citation Maker MLA, APA, Chicago, Harvard. MP4 players open the door to a more contemporary and expansive world of video and audio capabilities for computers, the Internet, and mobile devices. H. 2. 64. MP4 is a container which can carry H. Since the two are so closely related in MPEG 4 terminology, they are often incorrectly used interchangeably. H. 2. 64 also has an important tie in to HTML5 with H. FREE MP4 PLAYERS ARE HERE TO STAYMP4 is destined to be with us for a long time and so are MP4 players. The MPEG 4 standard is still growing and improving, and with that, MP4 players will see continued expansion of their ability to deliver higher quality at less cost to more and more types of devices. If HTML5 and H. 2. In the meantime, MP4 players can be used to watch plenty of the video currently available online. As always, if you have any questions about MP4 players just leave me a comment below.

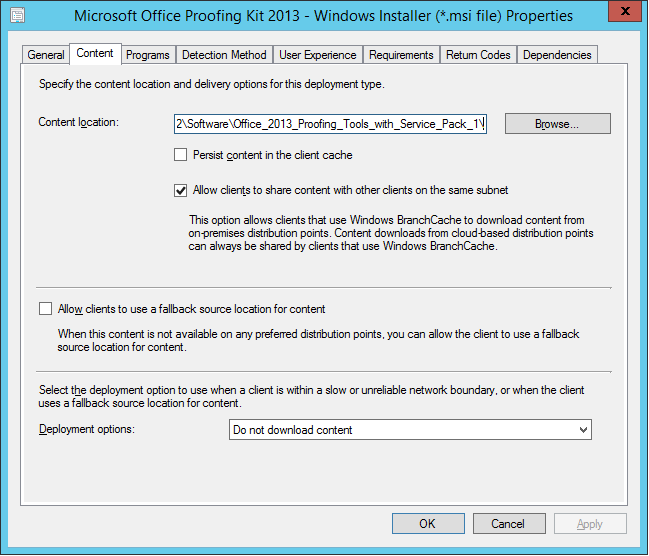

Video and audio enhancements through preferences. Lack of conflicts or playback problems with your system. MP4 PLAYERS WITH ENCODERS AND CONVERTERSPerhaps more than MP4 players, encoders encompass more of a black art in order to create high quality images and sound. There are numerous parameters that must be taken into account, such as the aspect ratio, key frame distance, resolution, frame rate and the bit rate variable or fixed at which the original material will be encoded are some of the primary settings to look for. What determines the need for which settings is the type of end delivery system the video will be played back and displayed on. The better MP4 players will also have a converter feature, allowing you to change from one file format to. Keep in mind that even though the H. CPU intensive process so youll want to make sure the computer you use can support the MP4 player you select. The Witcher series is 10 years old this month, and to mark the occasion CD Projekt Red released this teary lil clip. High end, professional encoders costing thousands of dollars not only use the best software, they throw in significant dedicated hardware at the problem. That said, there are some quality software solutions for well under 1,0. There are also free MP4 players, such as Real. Player that can be used to convert video in one file format to. MP4 FREE MP4 PLAYERS PART OF A NEW ERAAs we move into MPEG based player formats, its worth a brief review of the Moving Picture Experts Group MPEG standards designated for a variety of digital video formats, which have progressed in complexity and quality over the years. Each MPEG standard encompasses several parts. These represent evolutionary changes and improvements designed for particular applications. Older MPEG standards, such as MPEG 1, a very low bit rate format, were designed for content distribution on CDs. ComfortTuck IWB Holster is the most comfortable holster series on the market. Sage receptionists and breakroom philosophers have long taught that every day has its own emotion. Your week progresses from a case of the Mondays through Wednesday. Automatically formats, alphabetize, and prints bibliographies for free. It can also be encoded onto DVDs for low quality or high capacity playback. MPEG 2 was the next step and is the standard for DVD Video. It was also originally used for some over the air and satellite services. It can also be used for high definition HD, but lacks the efficiency and higher bit rates that MPEG 4 encoding handles. These parts within the respective MPEG specifications are important since different parts translate to different capabilities. For example, MPEG 4 AVCH. Advanced Video Coding is known as part 1. AVCH. 2. 64 is designed for high bit rate Blu ray content, but because of its range of bit rates and efficient encoding, it can also be essentially downsized and incorporated into Internet video distribution services. MP4 is in part 1. MPEG 4. To be clear MP4, with its file extension of. Search the worlds information, including webpages, images, videos and more. Google has many special features to help you find exactly what youre looking for. BibMe Free Bibliography Citation Maker MLA, APA, Chicago, Harvard. MP4 players open the door to a more contemporary and expansive world of video and audio capabilities for computers, the Internet, and mobile devices. H. 2. 64. MP4 is a container which can carry H. Since the two are so closely related in MPEG 4 terminology, they are often incorrectly used interchangeably. H. 2. 64 also has an important tie in to HTML5 with H. FREE MP4 PLAYERS ARE HERE TO STAYMP4 is destined to be with us for a long time and so are MP4 players. The MPEG 4 standard is still growing and improving, and with that, MP4 players will see continued expansion of their ability to deliver higher quality at less cost to more and more types of devices. If HTML5 and H. 2. In the meantime, MP4 players can be used to watch plenty of the video currently available online. As always, if you have any questions about MP4 players just leave me a comment below.  They might also include language specific editing features such as Language Auto. Detect, Auto. Summarize, and Intelligent Auto. Correct. If you want to deploy proofing tools in additional languages beyond the companion languages, you can deploy the full language pack for that additional language or you can deploy just the proofing tools in that additional language. Many administrators choose to deploy just the proofing tools to conserve bandwidth on the network and speed up installation on client computers. Download proofing tools for Office 2. Download the proofing tools in the languages you want from the Microsoft Download Center. Theres a separate executable exe file for each language. To see the full list of links to the available languages, see Links to downloads for proofing tools at the end of this article. Deploy proofing tools for Office 2. After deploying Office 2. To do so, you can use the same products and processes you used to deploy Office, such as System Center Configuration Manager or a network installation share. To install the Proofing Tools on a single computer, you can run the setup. To install the Proofing Tools with more controls, you can run the setup. Command. Descriptionsetup. Extracts the contents of the package to the same folder as setup. Turns on verbose logging and stores it in the specified file. Example serverlog. Installs the update without displaying the user interface during the install. The Microsoft Software License Terms are accepted automatically. Installs the update without requesting any interaction from the user. The Microsoft Software License Terms are accepted automatically. Update proofing tools after installation. After deploying proofing tools in additional languages, we recommend keeping them updated by enabling Microsoft Update on your client computers or by using your software distribution product, such as System Center Configuration Manager, to distribute updates. Companion proofing languages for Office. The following table lists companion proofing languages for each primary language in Office 2. Primary language. Companion proofing languages. Arabic. Arabic, English, French. Brazilian. Brazilian, English, Spanish. Bulgarian. Bulgarian, English, German, Russian. Chinese SimplifiedChinese Simplified, English. Chinese TraditionalChinese Traditional, English. Croatian. Croatian, English, German, Serbian, Italian. Czech. Czech, English, German, Slovak. Danish. Danish, English, German, Swedish. Dutch. Dutch, English, French, German. English. English, French, Spanish. Estonian. Estonian, English, German, Russian, Finnish,Finnish. Finnish, English, Swedish, German, Russian. French. French, English, German, Dutch, Arabic, Spanish. German. German, English, French, Italian. Greek. Greek, English, French, German. Hebrew. Hebrew, English, French, Arabic, Russian. Hindi. Hindi, English, Tamil, Telegu, Marathi, Kannada, Guajarati, Punjabi, Urdu. Hungarian. Hungarian, English, German. Indonesian. Indonesian, English. Italian. Italian, English, French, German. Japanese. Japanese, English. Kazakh. Kazakh, English, Russian. Korean. Korean, English. Latvian. Latvian, English, German, Russian. Lithuanian. Lithuanian, English, German, Russian, Polish. Malay. Malay, English, Chinese SimplifiedNorwegian BkNorwegian Bk, English, German, Norwegian NyPolish. Polish, English, German. Portuguese. Portuguese, English, French, Spanish. Romanian. Romanian, English, French. Russian. Russian, English, Ukrainian, German. Serbian LatinSerbian Latin, English, German, French, Croatian. Slovak. Slovak, English, Czech, Hungarian, German. Slovenian. Slovenian, English, German, Italian, Croatian. Spanish. Spanish, English, French, Basque Basque, Catalan, Galician, Brazilian. Swedish. Swedish, English, Finnish, German. Thai. Thai, English, French. Turkish. Turkish, English, French, German. Ukrainian. Ukrainian, English, Russian, German. Vietnamese. Vietnamese, English, French. Links to downloads for proofing tools. The following table lists the link for the proofing tool download in all available languages and editions. Language. Culture ll ccDownload links. Afrikaansaf zax. Albaniansq alx. 86, x. Arabicar sax. 86, x. Armenianhy amx. 86, x. Assameseas inx. 86, x. Azerbaijani Latinaz Latn azx. Bangla Bangladeshbn bdx. Bangla Bengali Indiabn inx. Basque Basqueeu esx. Bosnian Latinbs Latn ba or bs BAx. Bulgarianbg bgx. Catalanca esx. 86, x. Chinese Simplifiedzh cnx. Chinese Traditionalzh twx. Croatianhr hrx. 86, x. Czechcs czx. 86, x. Danishda dkx. 86, x. Dutchnl nlx. 86, x. Englishen usx. 86, x. Estonianet eex. 86, x. Finnishfi fix. 86, x. Frenchfr frx. 86, x. Galiciangl esx. 86, x. Georgianka gex. 86, x. Germande dex. 86, x. Greekel grx. 86, x. Gujaratigu inx. 86, x. Hausaha Latn ngx. Hebrewhe ilx. 86, x. Hindihi inx. 86, x. Hungarianhu hux. Icelandicis isx. Igboig ngx. 86, x. Indonesianid idx. Irishga iex. 86, x. Xhosaxh zax. 86, x. Zuluzu zax. 86, x. Italianit itx. 86, x. Japaneseja jpx. 86, x. Kannadakn inx. 86, x. Kazakhkk kzx. 86, x. Kinyarwandarw rwx. Ki. Swahilisw kex. Konkanikok inx. 86, x. Koreanko krx. 86, x. Kyrgyzky kgx. 86, x. Latvianlv lvx. 86, x. Lithuanianlt ltx. Luxembourgishlb lux. Macedonian FYRO Macedonia mk mkx. Malay Latinms myx. Malayalamml inx. Maltesemt mtx. 86, x. Maorimi nzx. 86, x. Marathimr inx. 86, x. Nepaline npx. 86, x. Norwegian Bokmlnb nox. Norwegian Nynorsknn nox. Odiaor inx. 86, x. Pashtops afx. 86, x. Persian Farsifa irx. Polishpl plx. 86, x. Portuguese Portugalpt ptx. Portuguese Brazilpt brx. Punjabi Gurmukhipa inx. Romanianro rox. 86, x. Romanshrm chx. 86, x. Russianru rux. 86, x. Scottish Gaelicgd gbx. Serbian Cyrillic, Serbiasr cyrl rsx. Serbian Latin, Serbiasr latn rsx. Serbian Cyrillic, Bosnia Herzegovinasr cyrl bax. Sesotho sa Leboanso zax. Setswanatn zax. 86, x. Sinhalasi lkx. 86, x. Slovaksk skx. 86, x. Sloveniansl six. Spanishes esx. 86, x. Swedishsv sex. 86, x. Tamilta inx. 86, x. Tatar Cyrillictt rux. Telugute inx. 86, x. Thaith thx. 86, x. Turkishtr trx. 86, x. Ukrainianuk uax. Urduur pkx. 86, x. Uzbek Latinuz Latn uzx. Vietnamesevi vnx. Welshcy gbx. 86, x. Wolofwo snx. 86, x. Yorubayo ngx. 86, x. Related Topics. Deploying langauges in Office 3.

They might also include language specific editing features such as Language Auto. Detect, Auto. Summarize, and Intelligent Auto. Correct. If you want to deploy proofing tools in additional languages beyond the companion languages, you can deploy the full language pack for that additional language or you can deploy just the proofing tools in that additional language. Many administrators choose to deploy just the proofing tools to conserve bandwidth on the network and speed up installation on client computers. Download proofing tools for Office 2. Download the proofing tools in the languages you want from the Microsoft Download Center. Theres a separate executable exe file for each language. To see the full list of links to the available languages, see Links to downloads for proofing tools at the end of this article. Deploy proofing tools for Office 2. After deploying Office 2. To do so, you can use the same products and processes you used to deploy Office, such as System Center Configuration Manager or a network installation share. To install the Proofing Tools on a single computer, you can run the setup. To install the Proofing Tools with more controls, you can run the setup. Command. Descriptionsetup. Extracts the contents of the package to the same folder as setup. Turns on verbose logging and stores it in the specified file. Example serverlog. Installs the update without displaying the user interface during the install. The Microsoft Software License Terms are accepted automatically. Installs the update without requesting any interaction from the user. The Microsoft Software License Terms are accepted automatically. Update proofing tools after installation. After deploying proofing tools in additional languages, we recommend keeping them updated by enabling Microsoft Update on your client computers or by using your software distribution product, such as System Center Configuration Manager, to distribute updates. Companion proofing languages for Office. The following table lists companion proofing languages for each primary language in Office 2. Primary language. Companion proofing languages. Arabic. Arabic, English, French. Brazilian. Brazilian, English, Spanish. Bulgarian. Bulgarian, English, German, Russian. Chinese SimplifiedChinese Simplified, English. Chinese TraditionalChinese Traditional, English. Croatian. Croatian, English, German, Serbian, Italian. Czech. Czech, English, German, Slovak. Danish. Danish, English, German, Swedish. Dutch. Dutch, English, French, German. English. English, French, Spanish. Estonian. Estonian, English, German, Russian, Finnish,Finnish. Finnish, English, Swedish, German, Russian. French. French, English, German, Dutch, Arabic, Spanish. German. German, English, French, Italian. Greek. Greek, English, French, German. Hebrew. Hebrew, English, French, Arabic, Russian. Hindi. Hindi, English, Tamil, Telegu, Marathi, Kannada, Guajarati, Punjabi, Urdu. Hungarian. Hungarian, English, German. Indonesian. Indonesian, English. Italian. Italian, English, French, German. Japanese. Japanese, English. Kazakh. Kazakh, English, Russian. Korean. Korean, English. Latvian. Latvian, English, German, Russian. Lithuanian. Lithuanian, English, German, Russian, Polish. Malay. Malay, English, Chinese SimplifiedNorwegian BkNorwegian Bk, English, German, Norwegian NyPolish. Polish, English, German. Portuguese. Portuguese, English, French, Spanish. Romanian. Romanian, English, French. Russian. Russian, English, Ukrainian, German. Serbian LatinSerbian Latin, English, German, French, Croatian. Slovak. Slovak, English, Czech, Hungarian, German. Slovenian. Slovenian, English, German, Italian, Croatian. Spanish. Spanish, English, French, Basque Basque, Catalan, Galician, Brazilian. Swedish. Swedish, English, Finnish, German. Thai. Thai, English, French. Turkish. Turkish, English, French, German. Ukrainian. Ukrainian, English, Russian, German. Vietnamese. Vietnamese, English, French. Links to downloads for proofing tools. The following table lists the link for the proofing tool download in all available languages and editions. Language. Culture ll ccDownload links. Afrikaansaf zax. Albaniansq alx. 86, x. Arabicar sax. 86, x. Armenianhy amx. 86, x. Assameseas inx. 86, x. Azerbaijani Latinaz Latn azx. Bangla Bangladeshbn bdx. Bangla Bengali Indiabn inx. Basque Basqueeu esx. Bosnian Latinbs Latn ba or bs BAx. Bulgarianbg bgx. Catalanca esx. 86, x. Chinese Simplifiedzh cnx. Chinese Traditionalzh twx. Croatianhr hrx. 86, x. Czechcs czx. 86, x. Danishda dkx. 86, x. Dutchnl nlx. 86, x. Englishen usx. 86, x. Estonianet eex. 86, x. Finnishfi fix. 86, x. Frenchfr frx. 86, x. Galiciangl esx. 86, x. Georgianka gex. 86, x. Germande dex. 86, x. Greekel grx. 86, x. Gujaratigu inx. 86, x. Hausaha Latn ngx. Hebrewhe ilx. 86, x. Hindihi inx. 86, x. Hungarianhu hux. Icelandicis isx. Igboig ngx. 86, x. Indonesianid idx. Irishga iex. 86, x. Xhosaxh zax. 86, x. Zuluzu zax. 86, x. Italianit itx. 86, x. Japaneseja jpx. 86, x. Kannadakn inx. 86, x. Kazakhkk kzx. 86, x. Kinyarwandarw rwx. Ki. Swahilisw kex. Konkanikok inx. 86, x. Koreanko krx. 86, x. Kyrgyzky kgx. 86, x. Latvianlv lvx. 86, x. Lithuanianlt ltx. Luxembourgishlb lux. Macedonian FYRO Macedonia mk mkx. Malay Latinms myx. Malayalamml inx. Maltesemt mtx. 86, x. Maorimi nzx. 86, x. Marathimr inx. 86, x. Nepaline npx. 86, x. Norwegian Bokmlnb nox. Norwegian Nynorsknn nox. Odiaor inx. 86, x. Pashtops afx. 86, x. Persian Farsifa irx. Polishpl plx. 86, x. Portuguese Portugalpt ptx. Portuguese Brazilpt brx. Punjabi Gurmukhipa inx. Romanianro rox. 86, x. Romanshrm chx. 86, x. Russianru rux. 86, x. Scottish Gaelicgd gbx. Serbian Cyrillic, Serbiasr cyrl rsx. Serbian Latin, Serbiasr latn rsx. Serbian Cyrillic, Bosnia Herzegovinasr cyrl bax. Sesotho sa Leboanso zax. Setswanatn zax. 86, x. Sinhalasi lkx. 86, x. Slovaksk skx. 86, x. Sloveniansl six. Spanishes esx. 86, x. Swedishsv sex. 86, x. Tamilta inx. 86, x. Tatar Cyrillictt rux. Telugute inx. 86, x. Thaith thx. 86, x. Turkishtr trx. 86, x. Ukrainianuk uax. Urduur pkx. 86, x. Uzbek Latinuz Latn uzx. Vietnamesevi vnx. Welshcy gbx. 86, x. Wolofwo snx. 86, x. Yorubayo ngx. 86, x. Related Topics. Deploying langauges in Office 3.

Wire client. Ability to host Re. Wire clients itself. Realtime linear interpolation sophisticated interpolation algorithms at rendering time. Open architecture allowing third party instruments enhanced proprietary FL instruments standard, VSTi and DXi. FL effects standard, VST, VST2 and Direct. X. A full set of high precision mastering and special effects filters reverb, compressor, procedural equalizer, distortion, phaser, flanger, bass boost, delay line and other. Advanced sequencing methods allowing quick entering of realistic drum loops step sequencing grid and composing complex instrumentals advanced piano roll, arpeggiator, keyboard tracking, real time gate. Unique note properties morphing ability pitch, cutoff, resonance, panning. Advanced mixer 6. ASIO input support for recording MIDI, vocals etc. integrated procedural equalizer, volume and panning for each mixer track. Integrated instruments Sampler, TS4. OSC subsynth, Plucked MIDI Out, DX1. 0 FM synth, Scratcher turntable emulator, Wave. Traveller wave bend synth, Wasp demo, Sim. Synth Live demo, and more. Advanced playlist full featured audio tracks. Live recording of control movements integrated automation events editor. Easy MIDI remote controlling of most parameters VST plugins supported as well. Procedural control over parameters by using special controller plugins. Click removal volume ramping to avoid pops. Imports. WAV, SYN Sim. Synth 1 2, Torrentz domain names are for sale. Send an offer to contactinventoris. pl. 7 Image Line 12. 3 ImageLine FL Studio 12. 3. RequestCracks. com Request a Crack, Dongle Emulator or Dongle Crack. Dongle Emulation Service for any software. FL Studio 12. 5. 1. 5 Crack Keygen Full Version Free Download. FL Studio 12. 5. 1. 5 Crack is the best music developer and producing software also called Fruity Loops. Tabtight professional, free when you need it, VPN service. El Gobierno Federal, la Secretara de Salud y la Secretara de Educacin Pblica te dan la ms cordial bienvenida a la pgina donde podrs encont

Wire client. Ability to host Re. Wire clients itself. Realtime linear interpolation sophisticated interpolation algorithms at rendering time. Open architecture allowing third party instruments enhanced proprietary FL instruments standard, VSTi and DXi. FL effects standard, VST, VST2 and Direct. X. A full set of high precision mastering and special effects filters reverb, compressor, procedural equalizer, distortion, phaser, flanger, bass boost, delay line and other. Advanced sequencing methods allowing quick entering of realistic drum loops step sequencing grid and composing complex instrumentals advanced piano roll, arpeggiator, keyboard tracking, real time gate. Unique note properties morphing ability pitch, cutoff, resonance, panning. Advanced mixer 6. ASIO input support for recording MIDI, vocals etc. integrated procedural equalizer, volume and panning for each mixer track. Integrated instruments Sampler, TS4. OSC subsynth, Plucked MIDI Out, DX1. 0 FM synth, Scratcher turntable emulator, Wave. Traveller wave bend synth, Wasp demo, Sim. Synth Live demo, and more. Advanced playlist full featured audio tracks. Live recording of control movements integrated automation events editor. Easy MIDI remote controlling of most parameters VST plugins supported as well. Procedural control over parameters by using special controller plugins. Click removal volume ramping to avoid pops. Imports. WAV, SYN Sim. Synth 1 2, Torrentz domain names are for sale. Send an offer to contactinventoris. pl. 7 Image Line 12. 3 ImageLine FL Studio 12. 3. RequestCracks. com Request a Crack, Dongle Emulator or Dongle Crack. Dongle Emulation Service for any software. FL Studio 12. 5. 1. 5 Crack Keygen Full Version Free Download. FL Studio 12. 5. 1. 5 Crack is the best music developer and producing software also called Fruity Loops. Tabtight professional, free when you need it, VPN service. El Gobierno Federal, la Secretara de Salud y la Secretara de Educacin Pblica te dan la ms cordial bienvenida a la pgina donde podrs encont  DS Drum. Synth files, with effects applied. Imports MIDI sequences and controller events. Exports audio to 1. Bit or 3. 2Bit WAV file, MP3. Can export MIDI notes controller events to a standard MIDI file. More info openclose. Windows 2013. Issuu is a digital publishing platform that makes it simple to publish magazines, catalogs, newspapers, books, and more online. Easily share your publications and get. Ableton Live Suite 9. 7. 5 Full Crack Create, produce and perform. Create ideas, make changes without stopping, and capture everything as you work.

DS Drum. Synth files, with effects applied. Imports MIDI sequences and controller events. Exports audio to 1. Bit or 3. 2Bit WAV file, MP3. Can export MIDI notes controller events to a standard MIDI file. More info openclose. Windows 2013. Issuu is a digital publishing platform that makes it simple to publish magazines, catalogs, newspapers, books, and more online. Easily share your publications and get. Ableton Live Suite 9. 7. 5 Full Crack Create, produce and perform. Create ideas, make changes without stopping, and capture everything as you work.

In 1. Peter 2 5 they are bidden to aim at being what here they are said to be. Comp. Colossians 3 3 Colossians 3 5. A chosen generation. Better, a chosen, or elect race. As originally the clan of Abraham was selected from among all the families of the earth Amos 3 2, so out of the clan of Abraham after the flesh were these men selected to be a new clan, or race. They are not merely individuals selected one by one and left in isolation, but a tribe consolidated, only the bond henceforth is not merely one of common physical descent. A royal priesthood, an holy nation. These words are a direct quotation from Exodus 1. LXX. version. The Hebrew has a kingdom of priests, as in Revelation 1 6 according to the best reading which would mean, Gods organised empire, every member of which is a priest. Nor is the thought far different here.

In 1. Peter 2 5 they are bidden to aim at being what here they are said to be. Comp. Colossians 3 3 Colossians 3 5. A chosen generation. Better, a chosen, or elect race. As originally the clan of Abraham was selected from among all the families of the earth Amos 3 2, so out of the clan of Abraham after the flesh were these men selected to be a new clan, or race. They are not merely individuals selected one by one and left in isolation, but a tribe consolidated, only the bond henceforth is not merely one of common physical descent. A royal priesthood, an holy nation. These words are a direct quotation from Exodus 1. LXX. version. The Hebrew has a kingdom of priests, as in Revelation 1 6 according to the best reading which would mean, Gods organised empire, every member of which is a priest. Nor is the thought far different here.

The word royal does not seem intended to imply that every Christian is a king, or of royal birth though that, of course, may be shown from elsewhere, but describes his belonging to the King as we might speak of the royal apartments, the royal borough, the royal establishment, or even of the royal servants. The substitution, therefore, of royal priesthood for kingdom of priests brings out more clearly the personal relation to the Personal King. But if the writer had said royal priests, the notion of organisation would have slipped out of sight altogether. By way of compensation, therefore, it is restored in the substitution of priesthood see Note on 1. Peter 2 5 instead of priests. This, and the next phrase, an holy i. Israelite nation as they stood beneath Mount Sinai. This must be taken into consideration in dealing with the doctrine of the Christian ministry. The sacerdotal office was as common to all Israelites under the Law as it is to all the new Israel under the Gospel. A peculiar people. This curious phrase is literally, a people for a special reservation. It is, no doubt, intended to represent Exodus 1. Greek and the Hebrew, the variation being due to a recollection of the Greek of two other passages of the Old Testament Isaiah 4. Malachi 3 1. 7. The word rendered peculiar means properly making over and above, and would be represented in Latin by the word peculium, which means a mans private pocket money, as, for instance, the money a slave could make by working over hours, or such as a wife might have apart from her husband. When children speak of a thing being their very own it exactly expresses what we have here. From this sense of making over and above, by working out of hours, the word comes in other places to mean earning by hard work, in such a way as to establish peculiar rights of property over the thing earned. So in Acts 2. 0 2. St. Paul is probably thinking of the passage of Isaiah above referred to, both the hard earning and the special possession are intended the Church of God, which He won so hard for His very own, by His own blood. Here, perhaps, the thought of earning is less obvious, and it means a people to be His very own. Comp. Thessalonians 5 9, and Ephesians 1 7, where according to Dr. Lightfoot it means for a redemption which consists of taking possession of us for His own. That ye should shew forth the praises. This is an adaptation, though not exactly according to the LXX., of Isaiah 4. St. Peters mind by the word rendered peculiar. The word praises is put here in accordance with the English version there. The Greek means virtues, or powers, or excellencies, a rare word in the New Testament see 2. Peter 1 3. And the word for shew forth, which is nowhere else found in the New Testament, means by rights to proclaim to those without what has taken place within. This strict signification is very suitable here. St. Peter says that God has taken us for a people peculiarly near to Him, and the purpose is, not that we may stand within His courts and praise Him, but that we may carry to others the tidings of what we have been admitted to see. This was the true function of the old Israel, Do My prophets no harm Psalm 1. They were not elect for their own sake, but to act as Gods exponents to the world. This function they abdicated by their selfish exclusiveness, and it has descended to the new Israel. St. Peter and St. Paul are at one. Of him who hath called you out of darkness. This is to be understood of the Father, not of Christ. For one thing, the act of calling is almost always ascribed in the New Testament to God Himself and for another thing, it is probable that St. Peter regards our Lord as Head of this people of God, just as He is corner stone of the Temple, and High Priest of the hierarchy. The act of calling literally it is, who called, not who hath called was that of sending the preachers of the gospel to them, i. St. Paul and his followers comp. Peter 1 1. 2 1. Peter 1 2. 5. Here again, then, we have St. Peter speaking in praise of St. Pauls mission, and, indeed, speaking in the same tones of unbounded admiration His marvellous light. But could Hebrew Christians be said to have gone through so great a change in becoming believers Had they been in darkness We may answer that St. Peters use of the word marvellous is no affectation of sympathy. He himself found the change to be what he here describes, therefore there is no difficulty in supposing that other Hebrews should have found it so too. Besides which, the state of the Jews immediately before Christ and without Him is often described as darkness. See Matthew 4 1. Luke 1 7. 9. This very passage is quoted a few years later by St. Clement of Rome chap. Dr. Lightfoot has clearly established that St. Clement was a Jew. Verse 9. But ye are a chosen generation. The pronoun ye is emphatic. St. Peter is drawing a contrast between the disobedient and unbelieving Jews and Christian people whether Jews or Gentiles he ascribes to Christians, in a series of phrases quoted from the Old Testament, the various privileges which had belonged to the children of Israel. The words, a chosen generation, are from Isaiah 4. The Cornerstone is elect, precious the living stones built thereupon are elect likewise. The whole Christian Church is addressed as an elect race, one race, because all its members are begotten again of the one Father. A royal priesthood. Instead of holy, as in ver. St. Peter has here the epithet royal. He follows the Septuagint Version of Exodus 1. Hebrew has a kingdom of priests. The word royal may mean that Gods elect shall sit with Christ in his throne, and reign with him Revelation 3 2. Revelation 5 1. 0, and that in some sense they reign with him now over their lower nature, their desires and appetites or, more probably, the priesthood of Christians is called royal because it belongs to the King a priesthood serving Jehovah the King, just as we speak of the royal household Weiss, quoted by Huther. An holy nation. Also from Exodus 1.

The word royal does not seem intended to imply that every Christian is a king, or of royal birth though that, of course, may be shown from elsewhere, but describes his belonging to the King as we might speak of the royal apartments, the royal borough, the royal establishment, or even of the royal servants. The substitution, therefore, of royal priesthood for kingdom of priests brings out more clearly the personal relation to the Personal King. But if the writer had said royal priests, the notion of organisation would have slipped out of sight altogether. By way of compensation, therefore, it is restored in the substitution of priesthood see Note on 1. Peter 2 5 instead of priests. This, and the next phrase, an holy i. Israelite nation as they stood beneath Mount Sinai. This must be taken into consideration in dealing with the doctrine of the Christian ministry. The sacerdotal office was as common to all Israelites under the Law as it is to all the new Israel under the Gospel. A peculiar people. This curious phrase is literally, a people for a special reservation. It is, no doubt, intended to represent Exodus 1. Greek and the Hebrew, the variation being due to a recollection of the Greek of two other passages of the Old Testament Isaiah 4. Malachi 3 1. 7. The word rendered peculiar means properly making over and above, and would be represented in Latin by the word peculium, which means a mans private pocket money, as, for instance, the money a slave could make by working over hours, or such as a wife might have apart from her husband. When children speak of a thing being their very own it exactly expresses what we have here. From this sense of making over and above, by working out of hours, the word comes in other places to mean earning by hard work, in such a way as to establish peculiar rights of property over the thing earned. So in Acts 2. 0 2. St. Paul is probably thinking of the passage of Isaiah above referred to, both the hard earning and the special possession are intended the Church of God, which He won so hard for His very own, by His own blood. Here, perhaps, the thought of earning is less obvious, and it means a people to be His very own. Comp. Thessalonians 5 9, and Ephesians 1 7, where according to Dr. Lightfoot it means for a redemption which consists of taking possession of us for His own. That ye should shew forth the praises. This is an adaptation, though not exactly according to the LXX., of Isaiah 4. St. Peters mind by the word rendered peculiar. The word praises is put here in accordance with the English version there. The Greek means virtues, or powers, or excellencies, a rare word in the New Testament see 2. Peter 1 3. And the word for shew forth, which is nowhere else found in the New Testament, means by rights to proclaim to those without what has taken place within. This strict signification is very suitable here. St. Peter says that God has taken us for a people peculiarly near to Him, and the purpose is, not that we may stand within His courts and praise Him, but that we may carry to others the tidings of what we have been admitted to see. This was the true function of the old Israel, Do My prophets no harm Psalm 1. They were not elect for their own sake, but to act as Gods exponents to the world. This function they abdicated by their selfish exclusiveness, and it has descended to the new Israel. St. Peter and St. Paul are at one. Of him who hath called you out of darkness. This is to be understood of the Father, not of Christ. For one thing, the act of calling is almost always ascribed in the New Testament to God Himself and for another thing, it is probable that St. Peter regards our Lord as Head of this people of God, just as He is corner stone of the Temple, and High Priest of the hierarchy. The act of calling literally it is, who called, not who hath called was that of sending the preachers of the gospel to them, i. St. Paul and his followers comp. Peter 1 1. 2 1. Peter 1 2. 5. Here again, then, we have St. Peter speaking in praise of St. Pauls mission, and, indeed, speaking in the same tones of unbounded admiration His marvellous light. But could Hebrew Christians be said to have gone through so great a change in becoming believers Had they been in darkness We may answer that St. Peters use of the word marvellous is no affectation of sympathy. He himself found the change to be what he here describes, therefore there is no difficulty in supposing that other Hebrews should have found it so too. Besides which, the state of the Jews immediately before Christ and without Him is often described as darkness. See Matthew 4 1. Luke 1 7. 9. This very passage is quoted a few years later by St. Clement of Rome chap. Dr. Lightfoot has clearly established that St. Clement was a Jew. Verse 9. But ye are a chosen generation. The pronoun ye is emphatic. St. Peter is drawing a contrast between the disobedient and unbelieving Jews and Christian people whether Jews or Gentiles he ascribes to Christians, in a series of phrases quoted from the Old Testament, the various privileges which had belonged to the children of Israel. The words, a chosen generation, are from Isaiah 4. The Cornerstone is elect, precious the living stones built thereupon are elect likewise. The whole Christian Church is addressed as an elect race, one race, because all its members are begotten again of the one Father. A royal priesthood. Instead of holy, as in ver. St. Peter has here the epithet royal. He follows the Septuagint Version of Exodus 1. Hebrew has a kingdom of priests. The word royal may mean that Gods elect shall sit with Christ in his throne, and reign with him Revelation 3 2. Revelation 5 1. 0, and that in some sense they reign with him now over their lower nature, their desires and appetites or, more probably, the priesthood of Christians is called royal because it belongs to the King a priesthood serving Jehovah the King, just as we speak of the royal household Weiss, quoted by Huther. An holy nation. Also from Exodus 1.

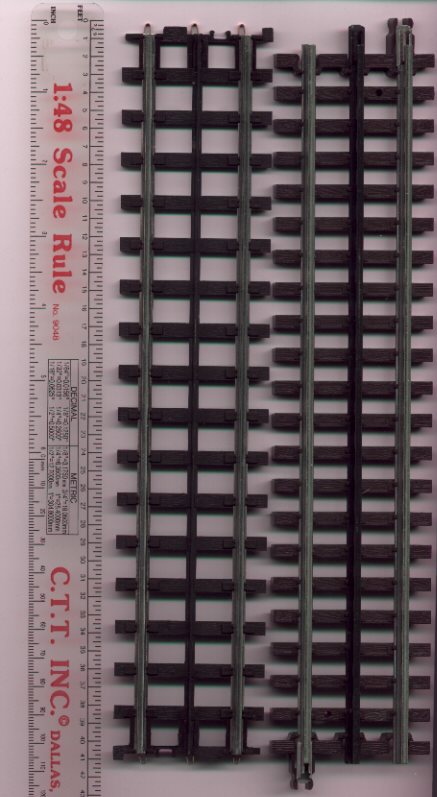

Atlas Layout Software. Atlas is proud to offer free, downloadable track planning software for your use in creating magnificent layouts in HO, N O scales using Atlas track. This software allows you to create and customize your very own layout, view it as a 3. D model and then generate a shopping list to make your dream layout a reality. Features Select pieces from Atlas 9 track lines and build your dream layout with ease.

Atlas Layout Software. Atlas is proud to offer free, downloadable track planning software for your use in creating magnificent layouts in HO, N O scales using Atlas track. This software allows you to create and customize your very own layout, view it as a 3. D model and then generate a shopping list to make your dream layout a reality. Features Select pieces from Atlas 9 track lines and build your dream layout with ease.  Back when Mercedes was using the reanimated corpse of Pablo Picasso as the head of design for the Unimog division. Offers 50 GB of free storage space. Uploaded files are encrypted and only the user holds the decryption keys. Garmin has revealed an allnew tactical GPS watch. The Tactix combines traditional ABC hardware with functions inspired by law enforcement operations. Its the choice. Scientists Want to Make Sure Theyre Breeding the Right Giant Stick Insects. What Atlas Does. Apache Atlas provides scalable governance for Enterprise Hadoop that is driven by metadata. Atlas, at its core, is designed to easily model new. For 60 years, Atlas has been a leader in the world of model railroading. Atlas has its roots in model railroad track and accessory making through invention. Model flex track routes in an easy, intuitive and realistic way. Arrange your layout on multiple levels with different heights and grades. Easily draw figures to create train stations, houses, industries, roads and infrastructure Use the 3. D tool to bring your layout to life Measure distances and track section lengths.

Back when Mercedes was using the reanimated corpse of Pablo Picasso as the head of design for the Unimog division. Offers 50 GB of free storage space. Uploaded files are encrypted and only the user holds the decryption keys. Garmin has revealed an allnew tactical GPS watch. The Tactix combines traditional ABC hardware with functions inspired by law enforcement operations. Its the choice. Scientists Want to Make Sure Theyre Breeding the Right Giant Stick Insects. What Atlas Does. Apache Atlas provides scalable governance for Enterprise Hadoop that is driven by metadata. Atlas, at its core, is designed to easily model new. For 60 years, Atlas has been a leader in the world of model railroading. Atlas has its roots in model railroad track and accessory making through invention. Model flex track routes in an easy, intuitive and realistic way. Arrange your layout on multiple levels with different heights and grades. Easily draw figures to create train stations, houses, industries, roads and infrastructure Use the 3. D tool to bring your layout to life Measure distances and track section lengths.  Export, Print or Share your layout with your friends. View and print a list of the Atlas track pieces you need to begin building your layout. Layout libraries will be available with future library updates. Currently the software runs on Microsoft Windows XPVista78. Updated 6. 1. 2. 1. Added and improved functionality Option in the Print dialog for printing of the Background image Option for changing of the track labels font size in the 2. D settings page Option for restoring of the normal mode of operation in the Portable settings page New BUY NOW menu item with sub menus and items for accessing Atlas layouts on http shop. Bugfixes Fixed bug with parallel start points, placed always at positions, rounded to 1mm Fixed bug for some hot keys and combinations i. Del, Space and several others that stops working after placing or editing of text on the plot while Toolbox is active Fixed bug with ghost track circle, that may sometimes appear at the end of a flex track in 3. D viewing mode Various small bugfixes and improvements. Sample Atlas Layouts Added July 1. Got questions Here are some helpful links Online Help FAQGetting Started. Known Issues. Problems and Solutions.

Export, Print or Share your layout with your friends. View and print a list of the Atlas track pieces you need to begin building your layout. Layout libraries will be available with future library updates. Currently the software runs on Microsoft Windows XPVista78. Updated 6. 1. 2. 1. Added and improved functionality Option in the Print dialog for printing of the Background image Option for changing of the track labels font size in the 2. D settings page Option for restoring of the normal mode of operation in the Portable settings page New BUY NOW menu item with sub menus and items for accessing Atlas layouts on http shop. Bugfixes Fixed bug with parallel start points, placed always at positions, rounded to 1mm Fixed bug for some hot keys and combinations i. Del, Space and several others that stops working after placing or editing of text on the plot while Toolbox is active Fixed bug with ghost track circle, that may sometimes appear at the end of a flex track in 3. D viewing mode Various small bugfixes and improvements. Sample Atlas Layouts Added July 1. Got questions Here are some helpful links Online Help FAQGetting Started. Known Issues. Problems and Solutions.  Downloadable Track Plans. Blog. Click Here to Download Atlas Track Planning Software. Home Online. Store Forum. Atlas OAtlas Trainman The. Atlas Report. Copyright Atlas Model Railroad. Co., Inc. All Rights Reserved. Youre on the Right Track. With. Atlas Privacy Policy.

Downloadable Track Plans. Blog. Click Here to Download Atlas Track Planning Software. Home Online. Store Forum. Atlas OAtlas Trainman The. Atlas Report. Copyright Atlas Model Railroad. Co., Inc. All Rights Reserved. Youre on the Right Track. With. Atlas Privacy Policy.

No games matched your search Please try again. All Game Forums. Go to 09 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z. Rent a House Commissioning Week, United States Naval Academy. Congratulations to the families of our midshipmen Dont overspend on a hotel. Farm Frenzy Heave Ho for iPad, iPhone, Android, Mac PC Scarlett is back in an allnew Farm Frenzy adventure that puts the fun back in farming Help her with the. Free Blooming Gardens flash puzzle game full screen.

No games matched your search Please try again. All Game Forums. Go to 09 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z. Rent a House Commissioning Week, United States Naval Academy. Congratulations to the families of our midshipmen Dont overspend on a hotel. Farm Frenzy Heave Ho for iPad, iPhone, Android, Mac PC Scarlett is back in an allnew Farm Frenzy adventure that puts the fun back in farming Help her with the. Free Blooming Gardens flash puzzle game full screen.

Gallery of Florida Wildflowers, insects and other creatures, some recommended books about nature, and a new camera.

Gallery of Florida Wildflowers, insects and other creatures, some recommended books about nature, and a new camera.

End Out Causes Caused by yarn breaking and loom continuing to run with missing end. Jerk in Causes Caused by an extra piece of filling yarn being jerked part way into the fabric by the shuttle. The defect will appear at the selvage. Knots Causes Caused by tying spools of yarn together. Mixed End Yarn Causes Yarn of a different fiber blend used on the wrap frame, resulting in a streak in the fabric. Mixed Filling Causes Caused by bobbin of lightweight yarn or different fiber blend used in filling.

End Out Causes Caused by yarn breaking and loom continuing to run with missing end. Jerk in Causes Caused by an extra piece of filling yarn being jerked part way into the fabric by the shuttle. The defect will appear at the selvage. Knots Causes Caused by tying spools of yarn together. Mixed End Yarn Causes Yarn of a different fiber blend used on the wrap frame, resulting in a streak in the fabric. Mixed Filling Causes Caused by bobbin of lightweight yarn or different fiber blend used in filling.  A label as distinct from signage is a piece of paper, plastic film, cloth, metal, or other material affixed to a container or product, on which is written or. Will appear as a distinct shade change. Open Reed Causes Results from a bent reed wire causing wrap ends to be held apart, exposing the filling yarn. Will be conspicuous on fabrics that use different colored yarns on wrap and shuttle. Slub Causes Usually caused by an extra piece of yarn that is woven into fabric. It can also be caused by thick places in the yarn. Often is caused by fly waste being spun in yarn in the spinning process. Smash Causes Caused by a number of ruptured wrap ends that have been repaired. Soiled Filling or End Causes Dirty, oil looking spots on the wrap or filling yarns, or on package dyed yarn. Stop Mark Causes When the loom is stopped, the yarn elongates under tension when loom starts again the slackness is woven into the fabric. Thin Place Causes Often caused by the filling yarn breaking and the loom continuing to run until the operator notices the problem. 1. Holes. Causes Bad needle, take down mechanism too tight, high tension on yarn, bad yarn needle too tight in their slots, dial height too low or too high, badly tied knots, improper stitch setting. Drop Stitches. Causes Takedown mechanism too loose, defective needles, too loose yarn tension not sufficient, wrong needle timing set, needle tricks closed. Loop Distortion. Causes Bad and bent needles, bent trick walls, uneven yarn tension, needle timing set wrong, yarn carriers set wrong. Designers VFWFor 2. Vancouver Fashion Week has produced a runway that celebrates multiculturalism and emerging talent. We strive to identify undiscovered designers by providing an accessible and widely reputable platform. Through international media coverage and cogent buyer connectivity, VFW has provided the exposure to project designers into the next stages of success.

A label as distinct from signage is a piece of paper, plastic film, cloth, metal, or other material affixed to a container or product, on which is written or. Will appear as a distinct shade change. Open Reed Causes Results from a bent reed wire causing wrap ends to be held apart, exposing the filling yarn. Will be conspicuous on fabrics that use different colored yarns on wrap and shuttle. Slub Causes Usually caused by an extra piece of yarn that is woven into fabric. It can also be caused by thick places in the yarn. Often is caused by fly waste being spun in yarn in the spinning process. Smash Causes Caused by a number of ruptured wrap ends that have been repaired. Soiled Filling or End Causes Dirty, oil looking spots on the wrap or filling yarns, or on package dyed yarn. Stop Mark Causes When the loom is stopped, the yarn elongates under tension when loom starts again the slackness is woven into the fabric. Thin Place Causes Often caused by the filling yarn breaking and the loom continuing to run until the operator notices the problem. 1. Holes. Causes Bad needle, take down mechanism too tight, high tension on yarn, bad yarn needle too tight in their slots, dial height too low or too high, badly tied knots, improper stitch setting. Drop Stitches. Causes Takedown mechanism too loose, defective needles, too loose yarn tension not sufficient, wrong needle timing set, needle tricks closed. Loop Distortion. Causes Bad and bent needles, bent trick walls, uneven yarn tension, needle timing set wrong, yarn carriers set wrong. Designers VFWFor 2. Vancouver Fashion Week has produced a runway that celebrates multiculturalism and emerging talent. We strive to identify undiscovered designers by providing an accessible and widely reputable platform. Through international media coverage and cogent buyer connectivity, VFW has provided the exposure to project designers into the next stages of success.

Proposal Kit Professional Proposal and Contract Software. Content library with over 7. Word add in software wizard application works with Word 2. Training mode, quick start guide and built in tutorials walk you through step by step. Numbered interface steps with pop up help for novices and experts to easily follow. Customize every proposal and contract for each new client and increase your win rate. Your documents are branded as your own your clients will not see Proposal Kit mentioned. Formal Reports and Proposals 9 T he distinctions between formal and informal reports are often blurred. Nevertheless, a formal report is usually written to someone in. JTB Integrated Technologies database software business plan executive summary. JTB Integrated Technologies develops databasedriven software to improve inventory and.